It’s 11am on the first day of my internship at Out of Joint, and there are six guns pointed at my face. Needless to say, this wasn’t quite what I’d expected.

Don’t worry, I hadn’t blown up the office, killed Dunbar the Out of Joint cat or even made a below par cup of tea; the guns aren’t real. I’m sitting in on a workshop with stage combat specialists RC-Annie, who are teaching a group of actors how to walk, talk and shoot like a group of real soldiers. They’re incredibly thorough, and the first twenty minutes of my day have been spent sipping a cup of tea while everyone else sweated their way through a military work-out (definitely something I could get used to). Then it was on to marching, hand signals, and how to load a gun. Over two hours I’ve seen the actors go from slumped on the floor with Dunbar to carrying out a covert operation in a war zone created out of a pile of plastic chairs.

This was the opening session for a week-long workshop Out of Joint’s upcoming play, Close Quarters. When I arrived, a survivor of university exam season, the production team were ready to bring in actors to start playing with the script. By seeing it up on its feet, and hearing the characters speak, they can take the project to the next stage of development. It’s a thrilling process; scenes are edited before my eyes, emotions change with a snap of director Kate Wasserberg’s fingers, and, on one fateful morning, a private is suddenly promoted to NCO, much to the (feigned) outrage of her colleagues.

As a budding playwright myself, watching Out of Joint’s creatives at work has been incredibly enlightening, and my small notebook soon proved inadequate. Kate leads a series of exercises designed to generate new material, and to examine how existing scenes look and feel off the page. In one of my favourites, the actors were recorded conversing about topics pertinent to the play, which I then transcribed for them. This not only revealed a glut of information about speech patterns in social situations, but also, in a conversation about arguments, prompted the director to confess to once attacking her friend with a duvet. Luckily, the office is a duvet-free zone, so I should make it to the end of the week unscathed.

It’s not all guns-blazing fight scenes: in between discharging of AK47s at enemies, relationships are put through their paces. One afternoon, the actors perform an extended improvisation. None of them are allowed to leave a “room” (again made of plastic chairs – they’re very versatile), but, throughout, are passed notes by the director, detailing the various stresses their characters are undergoing. For example, one soldier is ‘sick of the girls bickering’, while another thinks they ‘may have seen someone die’ earlier that day. Despite one character’s desperate attempts to lighten the mood with a hilarious game of ‘Would You Rather’, the tension soon becomes ready to cut with a knife. I’m on the edge of my seat as two friends I’d already become emotionally invested in begin to argue. I’m so caught up in the action that, when one girl pretends to vomit into the bin, I have to stop myself from jumping up to hold her hair back for her.

However, as exciting as the goings-on of the rehearsal room have been, they are not what has impressed me the most about Out of Joint: that has occurred around the large meeting table. Throughout my few short but incredible days here, I have had the chance to sit in on meetings about scripts in production, upcoming projects (no spoilers!) and even discussions of the current theatre scene. What has struck me most is the sheer amount of knowledge, energy and pure passion on display here, and, I promise you, great things are coming from this company.

]]>

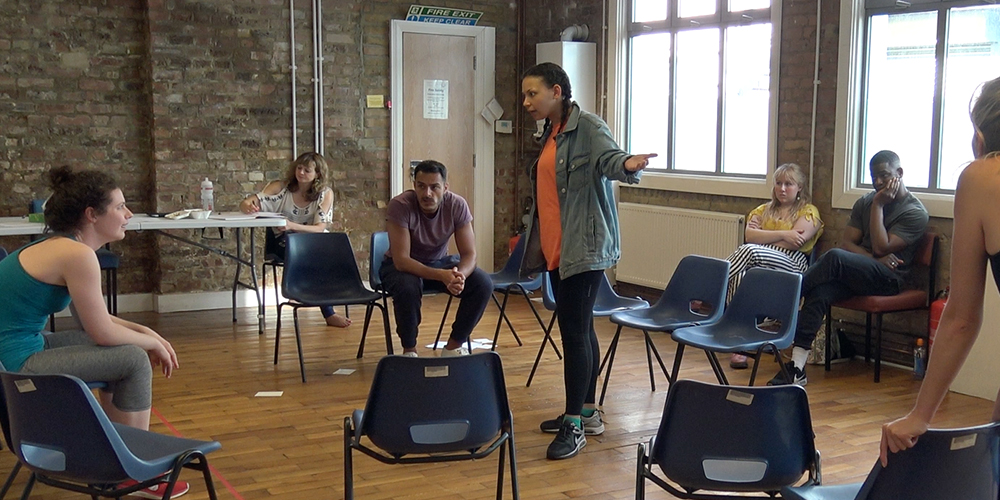

Some of the writers and actors involved in the Andrea Project

In late 2017, eight young women from Bolton and London worked with professional playwrights Laura Lomas and Rachel Delahay to make their own short plays for a performance at the Royal Court Theatre. This was The Andrea Project, a collaboration between Out of Joint, the Royal Court Theatre and the Bolton Octagon to coincide with our production of Rita, Sue and Bob Too. Its name is a dedication to the late playwright Andrea Dunbar, who was just 15 when she wrote her first play, and 19 when she wrote Rita, Sue and Bob Too.

Over six weeks the writers, who were aged between 15 and 19, developed their skills and the confidence to write about what matters to them, before writing a short play inspired by Rita, Sue and Bob Too. The pieces were performed to a full house at the Royal Court’s Theatre Upstairs on 20 January 2018.

We wanted to share their experiences with you, so Out of Joint has commissioned them to write a piece each for this blog. We hope you enjoy them. (The Andrea Project will return later this year – keep an eye on our education pages).

– Gina Abolins, Education & Artist Development Officer

Abi Earnshaw

The 20th of January 2018 was the best day of my life, full stop. Not only did I watch my very own short play being performed at The Royal Court Theatre but I also met several other amazing, female, creators and writers as well as the cast of ‘Rita, Sue And Bob Too’.

The process of all this started in October 2017 when a very nervous fifteen-year-old walked into the foyer in the Bolton Octagon Theatre to watch the controversial Andrea Dunbar play; ‘Rita Sue and Bob Too’. Now that was an experience! The following Tuesday, I returned to begin the writing process with three other fantastic young female writers. The next six sessions, led by playwright Laura Lomas, consisted of: intricate discussions about our world; talks about what it means to be a young woman from Bolton; reading various short plays; and developing our writing techniques.

The first few sessions were all about developing ideas and focusing on what was important to us that we could bring into our plays. Those sessions very much centred around Andrea Dunbar and her influence on young female writers. For me, this was the first time that I had been given freedom to write about anything I wanted to so I grabbed that opportunity and ran.

I had written plays before for GCSE drama and other extra-curricular groups but these had been in groups where I had the help and ideas from my peers. This was completely different and one hundred percent my own work, and boy was it hard. I had never been so obsessed with writing something. I became so attached to my characters that my already over-active imagination sucked me away from my life and school work and pushed me into the reality of my characters. There was no escape for me as my dreams led me to new ideas and themes that I could pull into my seven-minute piece; the options were endless. Eventually, after six weeks the sessions came to a sad close. We had a deadline two weeks later to e-mail Laura our first drafts which would be evaluated and sent back to us with written feedback before we submitted our final pieces on the 11th of December.

Just over one month later, I slowly got dressed and made myself look presentable before my mum and I got in her car to get our tram to Manchester Piccadilly before catching the train to London Euston. Everything was running smoothly until the train’s first stop where a rather clumsy woman with a large rucksack knocked my cup of tea onto my lap. We hadn’t been on the train for twenty minutes before something bad happened; it was just my luck. The rest of the journey passed by with ease and we soon found ourselves at the Royal Court Theatre. Climbing what seemed like ten thousand flights of stairs, we reached the Jerwood Theatre at the top of the building and quickly took our seats. Some quick words were said before the first play was announced; “Dear Tim, by Abi Earnshaw.” Glancing at my mum I could hardly contain my excitement as the actors took to the stage.

It was better than I could have ever imagined and as I sat through the rest of the fantastic plays, I couldn’t wait to thank the actors for playing my characters in the best way possible. The experiences from that day will stick with me for the rest of my life, especially watching ‘Rita, Sue And Bob Too’ whilst being sat next to my mum, and I am eternally grateful to everyone who made one of my dreams a reality.

Beatrice de Goede

Throughout my life, I have been conscious of my excessive worrying about the approval of other people and myself. It was not surprising that numerous people described me as a “worrier”. Second-guessing myself was a part of my nature. Writing had been an enjoyable past-time for me and in September, when I received the news that I was to be writing my very own play to be performed at The Royal Court Theatre in London, I was ecstatic.

When the writing workshops began with Laura Lomas, uncertain as I was, as I usually am when meeting new people, I found that I settled down strangely quickly. I am quite sure, looking back, that it was because of the perfect atmosphere that we were provided with: a small group of young women of a similar age. We all shared something in our similar experiences as young teenage girls and yet, we were all so radically different. The comfort I found in that room to talk and to discuss work of other writers and also our own feelings felt somewhat liberating. Very soon, Tuesdays (the day of the week that the writing group was held on) became the day that I would count down to every week.

Andrea Dunbar, the writer of The Arbor and Rita, Sue and Bob Too was the beginning of our journey, delving deep into various plays, traits of society and ourselves. Her seemingly comedic plays had clear themes of female oppression and abuse, enhancing the beliefs of our fully female group to also make a statement through words.

Reading through monologues of unconditional love, cryptic plays requiring deciphering and scenes in which argument’s fuse was just about being lit, I experienced more styles of writing than I had seen before. Reading these pieces, I found a desire to adopt my own style.

I believe that it was more than once, Laura told us that in order to write a play, we must shine the light of our own life through a prism to create a world of excitement not too far from our own. It was during my writing that I found myself fulfilling what Laura had said, as I hijacked characters and scenes from my own life in order to spark my own play. Slowly, the characters began to take on shape, growing apart from their originals as the story carved their personalities until they were much less like carbon copies of the people that I, myself, know. Not only was there a formation of a story, but a reflection on my own life buried deep inside.

As I sat on a seat (actually a bean bag) recommended by Ellie from the Royal Court as the best place to sit in the room, I watched my play, Red Light being performed by a very talented cast of professional actors. Watching them bring to life, characters and scenes based on my own life, the themes of pressure and expectations and desired freedom, touched me deep down. Having doubted my comedic values throughout my life, the laughter that my play created in that room filled me with a sweeping sense of pride, swelled even more with the great applause and appreciation that followed.

As I said, I had always been a bit of a worrier, but the confidence that this project gave me in myself and in my writing was absolutely incredible, and the visible impact that words can have on an audience was exhilarating. Yes, putting a piece of yourself out there is a risk, but the virtue of seeing people’s reactions and the impact of your words is a divine privilege. If ever I was given the opportunity again, I would grasp it with all my might, as the power of writing, in manipulating people’s emotions and extracting from them a communal sense of fear or love or anger or relief or anticipation, is a true gift that anyone would be a fool to overlook.

Ambrin McBrinn

It’s 12 pm on a Saturday afternoon. The windows of the coffee shop are foggy with condensation and I can’t stop picturing the air around me as breath. Boredom. Another school email. Click. Extracurriculars. Delete. The milk steamer screams. A toddler drops her plastic cup of marshmallows. Click. Playwriting opportunities? I scroll and skim-read the poster. The Royal Court Theatre, female voices, the world around us. Then I read it again and again until I decide that I have to try to apply. I think of all the things I want to write about.

I want to write about how standing in a crowd makes me feel so insignificant yet somehow so powerful. I want to write about how quickly I’m rushing through what I will one day refer to as ‘the good old days’, being forced to grow up faster then I can cope with.

I start typing a submission and by the time I stop it’s dark outside, I’m wrapped up in my own world and I’m pressing send. I’m shocked when I receive a phone call, and soon I’m counting the 13 stops from here to the theatre. Walking through the stage door, I’m nervous but excited to meet everyone. The workshops are an opportunity to learn about writing conventions while improving and sharing. The others are kind and insightful and witty, but above all, they are inspiring.

I’ve never written dialogue before but it’s been a few hours and I’m already cramming letters into margins and between chunky scribbles. It is both more difficult and more rewarding than I thought it would be. I’m learning how to explore ideas without being afraid of making mistakes, everything can be redrafted until I find the right words in the right order. I find that my favourite lines come sporadically and surprise me, born through mistakes. I want to write about the warm tingle that travels from my toes up to my cheeks when I try something new and realise I love it. I’m learning about how to create the feelings I experience when watching a play, thinking about how I can manipulate time and space to create my own effects. I’m learning that vulnerability or confusion or embarrassment in everyday life is good, I can use these feelings to fuel my writing.

I want to write about things that matter to me, and I am with people who will help me do it.

After many emails, another draft, a meeting, another two drafts, inspiration, and a final draft, I’m finally happy with what I have made. I have remoulded and reshaped characters, I have written variations and considered abstract conversations. Ultimately, I can’t quite believe I’ve written a play. It feels a bit surreal, I want to pinch myself. I want to do it again and again. I’ve decided to write about the realities of my life, the nuanced moments that define me, ones I so often overlook.

It’s 12 pm on a Saturday afternoon and I’m sitting in the Royal Court Theatre. I’m watching professional actors bring my words to life in a way that I hadn’t even thought of, a way that was better than I could’ve ever imagined. I am so excited and enraptured that I realise I’m holding my breath. I don’t want to miss a single second. Around me are the others, I watch as the initial ideas they shared with me have bloomed into even more captivating, poignant storylines and I can’t help but smile. I know this is a moment that I will look back on for a long time. I’m feeling lucky, and totally engaged, but most of all I’m feeling inspired. Tremendously inspired.

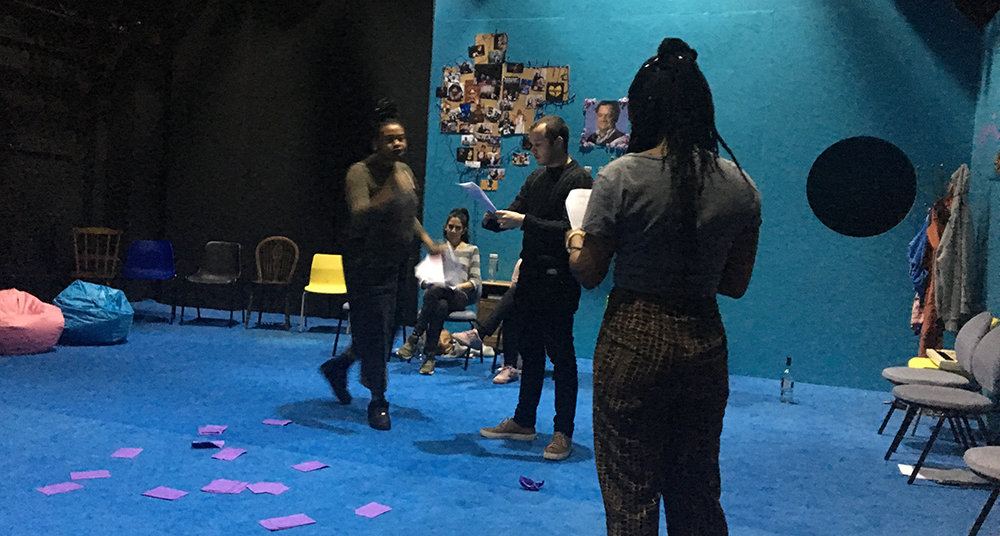

The performance in rehearsal at the Royal Court.

Caitlyn Vining

London is one of those places I’ve been desperate to visit for a really long time and finding out that I was taking part in the opportunity of putting my work on a stage in London was amazing news.

Writing has been a passion of mine for years. I’ve written plays and short stories before but never done anything with them. Then Ian Townsend a playwright I’ve work with at the Octagon Theatre Academy nominated me to go forward and share my work with the world.

Writing has been a passion of mine for years. I’ve written plays and short stories before but never done anything with them. Then Ian Townsend a playwright I’ve work with at the Octagon Theatre Academy nominated me to go forward and share my work with the world.

The workshops with Laura started and I was nervous at first to share my work because I didn’t know what she would think. My piece was inspired by some life experiences. Witnessing domestic violence and having friends bring out my good side. We got told to write about our life experiences but through the eyes of a made up character. The workshops were interesting and we learnt about Andrea Dunbar and her difficulty of being unaccepted in what she wanted to do with her life. Learning about this was a very emotional journey and I have found a new inspiration for what I write in the future. I will hopefully keep writing and will remember everything I’ve learnt on this journey. I have gained more confidence during this process and just to put something on stage that I have written is massively crazy.

On my travel down to London I was looking over my play having doubts about it, thinking that it is no good or questioning what if people don’t like it? But when it was performed I was shocked at how many laughs it got and how many people came up to me afterwards and said how brilliant it had been written. It was performed by great actors and came across just how I would have directed it.

When I walked into the Royal Court Theatre my face lit up and I knew that this was the start of my ambition. The staff were amazing and were very welcoming. Just from walking in it felt like I was home.

Watching Rita, Sue and Bob too for the second time in London was another amazing thing that took place in the day but talking to most of the cast members were unreal. The way Taj Atwal and Gemma Dobson portrayed the characters of Rita and sue was really interesting to watch as being a 16 year old myself made me think that any teenager my age could be experiencing what they go through on stage, and the way they did this was really inspirational.

James Atherton who played the role of Bob has been an actor who I’ve looked up since he was in Hollyoaks. When he asked me who it was inspired by, I answered with “I think that I was inspired by some life experiences and that domestic violence and friendship come together very nicely.” He replied with “ I think you have a good ear for dialogue and that Its like I have a piece of Andrea Dunbar in my work.” this shocked me because I never thought that I would get words like that from a professional and an inspiration of mine. I also loved how my catchy title was remembered by Samantha Robinson.

So this was a journey of a lifetime experience that I will honestly never forget and another ticked off my bucket list and I will never stop smiling about It. This won’t be the end of me and my work.

Katy Hamer

As part of the Andrea Project, I was involved with the Octagon Theatre in partnership with Out of Joint in a writing group of four girls from Bolton. We are all the same age and through a series of weekly writing workshops we developed our own characters, settings, plots and drafted our own plays.

After the workshops finished, we were invited down to London where we saw our own plays along with four other girls from London performed through rehearsed readings by a professional cast. After the readings, we watched Rita, Sue and Bob too and had a Q&A with the cast, some of which had watched our plays be read out. We asked them questions such as the best parts of our plays etc and it was overall a good experience.

My play was called Gray, and was about the experience of grief and the breakdown of relationships that can occur when friendships and such are put under strain. The inspiration for the play was that helping people who are going through grief, particularly young people as were the characters in my play, is a thing that as a society and a community we need to pay more attention too.

I tried to portray the fact that their grief was perhaps not taken seriously because they are young in age and are presumed to be immature by some. I wanted to show that mental health should be taken more seriously, not just in young people but across all ages and all people.

Trying to display the grief that these characters were going through was particularly hard, especially because I’ve been thankful enough to never have to cope with something as tragic as losing your best friend; I tried to show that sometimes they’ll begin to enjoy themselves and remember their situation and try not to be happy, which in my opinion is something a lot of people coping with grief go through. They try not to be happy because they should be sad, and i tried to show the message that being happy is okay, even in the darkest of situations.

Across the project, I’ve learnt a lot, especially that sharing your writing with others is not a bad thing. At the beginning of the workshops, I was very nervous about sharing what I’d written and reading out what I’d come up with, but now I’m becoming more confident in sharing my work, from family to friends and now online too. This is a big achievement for me, and it’s all thanks to the workshops and the help of the other girls in the project with me.

Writing the play was hard to say the least, I think I wrote around seven drafts for Gray and then three drafts of a completely different play I’d written that eventually got scrapped. There were edits and re edits, countless changes in dialogue and pages of character building to try and get it just right. It was difficult but it was worth it.

As the project comes to a close, I feel I have a lot I can take away from it. I have a cast of developed characters, each with a backstory and a friendship dynamic that I can expand on. I definitely think their stories will be expanded on and made longer in different forms of writing say short stories.

I will also be taking away a range of skills, from different character building exercises to setting building to developing descriptions and creating well rounded, interesting characters and plots.

Taking part in this project is one of the best things I’ve ever done, the results were incredible including being interviewed on TV! I’m so thankful for the opportunity and I hope it will lead to more writing opportunities in the future.

Writing, Struggling and Believing Too by Beattie Green

Towards the end of last year, wallowing in the tired dregs of a long autumn, I found myself in a peculiar position. Faced with the opportunity to write my own short play and say whatever I wanted about something, I found that in reality I had very little to say about anything. At all. For years I had been searching, like many young people do, for an opportunity to use my voice and when that perfect opportunity had at last arrived I anxiously opened my mouth to speak. What came out?

A tentative spluttering;

an incomprehensible mesh of half-formed words;

an inaudible whisper.

I had nothing to say.

Several weeks of workshops and research had revealed to me the power of the female voice and I had become more and more excited about its growing recognition in theatre. However, in tandem, I had become more and more certain that my voice couldn’t possibly be a part of that beautiful chorus. So many people around me seemed to be alive with a boiling, scorching passion and I felt, at best, like a tepid cup of coffee. Decaf coffee.

With this uncomfortable feeling brewing inside me I sat down to try and fathom the opening lines of my short play. The pixels of my laptop’s screen taunted me, fizzing in and out of reds, blues and greens. Tentative fingertips tensed over the keyboard and then, eventually, relaxed. I couldn’t do it. I shut the lid of my laptop and let my mind drift. I wondered whether laptops really have lids? Or is it just tops? Whether I would, after finishing my play, end up writing an underwhelming blog post about the process? Whether it was really that important for a play to have a message after all? Whether a message makes a play or a play makes message? Message didn’t seem like a real word anymore. I was overthinking.

This process of deliberation, doubt and dawdling stretched on for some weeks. I knew that, unlike a blog post, I couldn’t rely on alliteration to give my play some semblance of professionalism. So I turned, as we all do in the end, to some old friends – Rita and Sue. Oh, and Bob too. Andrea Dunbar’s play had, after all, been the inspiration of the project and I had adored mining it for useful new phrases, including “he’s a right fit-bit” and “dirty husband-pinching bastard”. ‘Rita Sue and Bob Too’ is a work rich with such hauntingly beautiful phraseology but it is also dense with important storytelling lessons. The experience of reading this play equipped me with the following tips which allowed me to get over my writer’s block:

Say what you see – although not completely autobiographical, it’s hard to deny that Dunbar’s works are inspired by the life that she led. For me, the process of writing became a lot less daunting when I realised that there wasn’t actually that much for me, as the writer, to do. The magic intrigue I needed to forge a compelling story was already there, readily available all around me. All I had to do was quietly observe and then, later, write. I began to hoard other people’s stories for my own use, like a nosy magpie, except I was thieving compelling narrative arcs instead of shiny stuff.

People are funny – as I tuned into the stories of those around me I realised something important. People are funny. They say strangely candid things through weird and unexpectedly profound amalgamations of words. They are blissfully ignorant of their own poetry and I decided that from then on I would be ready. Ready and waiting to steal the genius of the unknowing poet in every friend, relative and stranger.

Just get on with it – my greatest struggle when writing this play, and in life generally, is that I overthink everything. Chronically. But there is something about Andrea’s writing style, a distinctively uninhibited note, that seems to suggest an absence of agony and frustration in her process. In many ways Dunbar had a tumultuous and difficult life but her writing acts as an incredible contrast to this. It seems to me simple, untainted and honest. I wanted to achieve something similar, and how could I if I didn’t just get on with it?

So I did. I finally wrote the play. I still don’t know whether it has a message and, if so, whether that message is even valid or at all interesting or in any way new. But I do know one thing for certain. I wrote a play. I did it. And so, even if I didn’t have something to say, I definitely had something to share. And, above all, I loved experiencing what everyone else had to share at the project gala.

le livre des révélations by Jess Steadman

Jess enters stage right.

She is dressed in an embarrassing school uniform, she is the only member of the group younger than 18 and has come straight from school. She is halfway through the process, she has attended three workshops already and is so far thoroughly enjoying it all. But this time, somehow, it’s different.

She thinks back to the second workshop and her spectacular victory at ‘truth truth lie’, she supposes an advantage of being the baby of the group is that your lies are more believable as they don’t ever feature links and liquor. She remembers feeling pushed out of her comfort zone when she was given her first writing task; a series of questions designed to probe deeper and deeper into her insecurities and subsequently allow for the creation of more convincing characters. It might have been uncomfortable but boy, her characters were better in the long run.

But this time it’s different, she feels like an outcast, small and stupid. She starts writing…

Her writing hasn’t changed, only what she is wearing, and she really would be shallow if she let her clothes become a label. She was younger than the others, she was still in school and she was in a lilac tartan kilt but why should that become a disadvantage? If anything, her ‘naivety’ was something the others couldn’t even pretend to have.

Perhaps it is something that her characters could have?

The final workshop. Everybody is discussing what makes each one of our voices important, what makes us unique. She doesn’t know what makes her unique, she’s average when put against the backdrop of girls like her…

She feels like a schizophrenic half the time with the amount of voices whizzing about in her head when she has to make a decision. It’s not a mental illness, that’s her brash voice talking, it’s just human nature.

Jess…

‘Pick up your pen, start writing’

20th January, performance day. Raining.

Jess enters stage left, thankfully not in her uniform. She knows she is still the youngest writer in the room… but this time she doesn’t care.

She’s nervous, of course. She supposes it’s like handing your new-born baby to another mother to raise and then visiting them twenty years later when they are a fully-fledged adult. She hopes that this ‘mother’ has done a good job. She thinks of all the things she could have changed.

The lights are dimming, it’s starting. The actors are on stage, but she can’t tell who will be playing who, she hopes they’ve cast Izabelle right…

The final revelation

She needn’t have worried.

Finis

Thank you to Out of Joint and the Royal Court Theatre for this phenomenal experience.

Jasmine Jones

“The facts are there….You write what’s said, you don’t lie.”

Said a young Andrea Dunbar, who at 26, was a woman of many accomplishments: not only had she written two plays (The Arbor and Rita, Sue and Bob Too) which both premiered at The Royal Court she somehow managed to balance this with being the single mother to two children. I was first introduced to Andrea Dunbar in a very factual way indeed, when I was 17 I watched the documentary The Arbor, having not heard of Andrea before nor having read any of her work. The documentary struck a chord in me as a young, aspiring writer driven by a passion to tell the stories of people in my community and my life and reflect their truths honestly and on the scale they deserved as Andrea had.

Just over a year later I became aware of a revival of Andrea’s sophomore play Rita, Sue and Bob Too and simultaneously a writing group for young women that was to be attached to the production. Remembering the strong resonances the film had with me I was eager to apply to the course and luckily was accepted. All I knew before entering the building for the first session was that the writing group would bring together eight young women, four from London (myself, Ambrin, Jess and Beattie) and four from Bolton (Abi, Beatrice, Katy, Caitlyn) to be mentored and taught skills by two professional writers Rachel De-Lahay – who would lead our sessions in London – and Laura Lomas – who would lead the sessions in Bolton, with a view to writing short plays by the end. Admittedly, I was curious about the impact that us all being of the same gender would have on the sessions: Would there be a discernible difference between this group and other writing groups I had been a part of? Would discussions around gender and gender disparities have a bearing on the work we produced and ended up writing for our plays?

Drawing on Andrea’s commitment to telling the truth, we began our first session with introductions albeit with a tinge of fallacy…. We played Two Truths and a Lie, a game whose title belies its content all too well. This game effectively set the precedent for what we would be doing with Rachel over the next couple of months, drawing on truths and fleshing them out with a bit of fiction: good old-fashioned playwriting. In the sessions Rachel, with the help of Ellie, helped us solidify the two pillars of playwriting: the sourcing and discovery of an idea followed by its crystallisation using technique and craft. Our discussions connected pop culture to politics and capitalism to cultural appropriation. Rachel created a space where these discussions were frank and it ought to be said despite us all identifying as women did not at all guarantee us having the same opinions on issues! The beautiful thing about the group was how our different experiences in life informed the creative energy of the room. Disagreement was key in forming the bones of our writing, at least for me, as I wholeheartedly believe conflict is the basis of all drama. Whilst having one of these big discussions to help us come up with material, the subject of the Kardashians came up and more specifically Kylie Jenner. What proceeded was a big group discussion on the ethics of reality TV and living your life in the public eye as a young woman. It was in that moment, I came across the nub of the idea for my short play, I wasn’t absolutely sure what it was yet but I knew it would live at the intersection of race and gender under the lense of the viral nature of social media.

Fast forward to mid-January and our short plays were premiering as staged readings on the Royal Court Upstairs stage: I was filled with a mixture of nerves, excitement and curiosity as to how they would be received by the audience. What unfolded was beautiful. Stories were being told onstage that were of direct concern to us as young women – and they were not only about subjects stereotypically attributed to our demographic – but would serve to reflect the full span of our intellect, abilities and nuances. In spite of all this, one thing continued to trouble me after watching the playreadings – what had been the source of my nervousness in the first place?

Was it the fear of my play’s rejection or misunderstanding by the audience? Partially. But then what was behind this?

I began to realise that the root of my doubts and worries stemmed from one of the first questions that came up in our sessions with Rachel: What is inherently dramatic and what is worthy of being onstage?

The two characters of my play were two 20-something Black British female students – characters I don’t often, if ever, see onstage and the drama my protagonist Savannah was facing was, in effect, was a smearing by way of social media. Those characters and that story is not one I have often come across on the British stage but know all too well in day to day life. Immediately after seeing my play being read, against my better self I began to question the legitimacy and right of those characters being represented onstage.

I began to think that the reason for the scarcity of representation of stories like that with characters like that was because they just weren’t theatrically interesting enough.

Then, Andrea’s words for all those years sprung to mind: “The facts are there….you write what’s said, you don’t lie.” It was then I realised that my duty as a writer is to tell the truth of what I see around me as I see it and not be unhelpfully concerned with how it will be received by an audience. My primary focus should be reflecting the voices of those I see and know honestly. It is only through this that theatre can serve its purpose and hold a mirror up to the whole of society and it is perhaps only in this way it can reflect the most grossly underrepresented parts of society: which is exactly what Andrea stood for.

If the stories that are relevant to me and people like Andrea aren’t being told, me and young women like me must write them.

]]>Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett on Andrea Dunbar’s extraordinary portrait of teenage girls Rita, Sue and Bob Too, at the Royal Court Theatre from 9 January, then touring.

Taj Atwal and Gemma Dobson in our production. Photo by Richard Davenport.

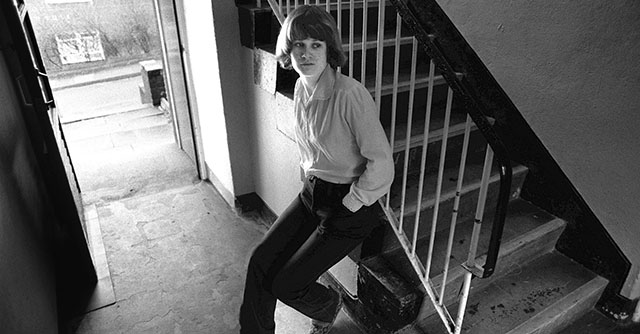

To have a play produced for the Royal Court at the age of 19 is an astonishing achievement. For it to be your second play (the first, The Arbor, having been written by Dunbar at 15 about her teenage pregnancy and subsequent stillbirth, was also put on at the Royal Court), and for you to be a working class woman from one of the roughest council estates in Bradford is a rise of astronaut proportions. Even now, a class ceiling ensures that voices like Andrea Dunbar’s are largely absent from the arts, perhaps even more so than they were in 1982 when Rita, Sue and Bob Too was first staged.

Times have changed since the Thatcher era, but not so much that modern audiences will struggle to recognise the world Dunbar draws with such raw humour. We have a different female Tory prime minister in 2017, but one who equally seems to believe there’s no such thing as society. As food bank use rockets and the younger generation face a housing crisis, the conservatives’ austerity policies continue to hit the most vulnerable.

Some will look at the world Dunbar came from – the Buttershaw estate where she continued to live until her premature death at the age of 29 was one of the poorest in Bradford – and marvel that she found anything to laugh about. Her semi-autobiographical tale of the friendship between two teenagers, Rita and Sue, and their “affair” with the older, married Bob which begins when he drives them home from babysitting his children crackles with sharp humour. Self-pity is entirely absent; Rita and Sue seem to be in possession of their own sexualities, yet are innocent by the standards of today’s teenagers, who can have porn clips beamed into their smartphones at a moment’s notice. They are also, obviously, under the age of consent, and though this is referenced, their relationship with the sleazy Bob is viewed by the girls themselves as bleakly but amusingly par for the course. A succession of abuse scandals that have come to light may have left you wondering whether the concept of grooming existed in 1982. Dunbar implies that the answer is not simple, though audiences may disagree. In a way it is courageous and perhaps controversial to stage this play now.

Andrea Dunbar. Photo: Don McPhee

Rita and Sue have the cocky sexual self-assurance of girls who’ve been fumbling since their early teens, yet neither knows how to put a condom on (Rita is even too embarrassed to buy sanitary towels), nor are equipped with the resilence or maturity to deal with the fallout of their sexual relationships with Bob. When it all finally falls apart, it is they who are left shouldering the blame as “sluts” who should be ashamed of themselves, while Bob is largely exempt – even his wife accuses them of putting it on plate. There’s a feeling that this is just how men are, nothing but trouble, unable to control themselves when tempted.

What makes Rita, Sue and Bob Too so successful as a piece of drama is its confrontational and unsentimental presentation of the characters; there is nothing “actorly” about them; these are real people, you can tell from the way they speak, and joke, and most of all swear. “This is life, the facts are there … these things do go on – maybe not in every circle, but certainly in mine”, Dunbar told the Yorkshire Post. To audiences who saw the much-loved film adaptation, this was “Thatcher’s Britain with her knickers down”, but to Dunbar there was little shocking about it, it was just the way things were. Her ambivalence, her refusal to moralise, and her insistence on portraying Rita and Sue’s lust for life despite their grim surroundings.

Class is a constant undercurrent in the play. Bob is married, employed, aspirational, from a posher part of town. He and his wife Michelle have the funds to pay two local girls to babysit while they enjoy evenings out. Michelle is a machinist and part-time Avon lady with a wardrobe full of the kinds of clothes that others can only dream of. Meanwhile Rita and Sue are about to leave school and are on YTS at the mill. “She’s got everything a woman could ask for,” says Rita. “Her own house. A nice husband and a couple of kids. She can buy what she wants. And still she’s not satisfied. I wouldn’t mind what she’s got. I’d be satisfied.”

Taj Atwal, Gemma Dobson and James Atherton in our production. Photo by Richard Davenport.

The affair ends up, in a way, providing both Rita and Sue with a passport out of the estate – Rita to what she hopes will be a more comfortable, middle-class life with Bob (though he has fallen on hard times and lost the biggest symbol of his sexual prowess – his car), and Sue to a new relationship with a fella you assume is more age-appropriate. She says that she misses the estate, but what it turns into over the years is something even worse, with booze and glue-sniffing replaced by heroin. In A State Affair, a play based on interviews with residents that was commissioned in 2000, audiences returned to the Buttershaw estate to discover that it was, if possible, even grimmer up North. “[Today] Rita and Sue would be smack heads… on crack as well… and working the red light district, sleeping with everybody and anybody for money. Bob would probably be injecting heroin”, said Andrea Dunbar’s daughter Lorraine, at the time. She went on to be convicted of manslaughter after her one-year-old son ingested her methadone.

The world of Rita, Sue and Bob Too could be seen as rather innocent in comparison. At the time the play was first performed, there were some residents of the estate who took objection to its portrayal, but what Dunbar did is hold a mirror up to her world with a lack of sentimentality that was defiant and courageous. She was one of seven children, with an abusive father, and by 18 was a single mother with three children of her own and living in a women’s refuge in Keighley. She could have so easily fallen by the wayside, as so many other working class kids with potential do. Instead, she became “a genius straight from the slums” who refused to shy away from uncomfortable and unpalatable truths, shocking Southern audiences and prompting them to ask, “is this really how people live?” Allegedly at least one critic believed it to be satire. It wasn’t so much kitchen sink drama as backseat of a car drama – filthy and funny, gritty and depressing, sexual yet hilariously unerotic, not to mention confrontational. Rita, Sue and Bob Too is full of the contradictions of poverty, a condition that to outsiders can seem two-dimensional at best. The play has a nuance that’s lacking from modern, reality TV depictions of life in benefits Britain, a country in which as far as much of the media is concerned there are scroungers and strivers and nothing in-between.

In 2017, the country is going through a period of soul-searching in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. Politicians and commentators no longer see it as politically convenient to ignore communities such as Dunbar’s. The Buttershaw has seen millions of pounds of regeneration money poured into it in the wake of the play and the film’s success, but it’s doubtful that it will have been enough to reverse decades of industrial and economic decline. A revival is timely. Rita and Sue’s live’s are as real and their problems as relevant today as they ever were.

Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett is a Guardian columnist and author based in North London. @rhiannonlucyc

Rita, Sue and Bob Too tours until February 2018.

]]>

photo by Helen Murray

Taj Atwal stars as Rita in our new production of Rita, Sue and Bob Too, Andrea Dunbar’s iconic play. Read about Taj’s first encounter with the work of a young woman who would come to be her favourite playwright.

I was a loud, passionate 18 year old heading off to drama school in leafy Surrey. It was a world away from North Yorkshire but I was fearless and streetwise, and felt I’d be able to settle in with no issues. But drama school was, it turned out, a world unknown to me. Sat in a circle on the first day we were asked to say one fascinating thing about ourselves and what we had been doing that summer. Teens shared stories of backpacking on their gap year around Vietnam, Cambodia and the Americas, others reeled off Shakespeare plays they had seen at the Globe. I muttered something about my own summer highlight, a trip to see my idols, the Spice Girls.

Some gasped, most laughed. I wanted the ground to swallow me whole. For the first time in my life, I was aware of a class divide, and it set me up for three years of feeling inadequate. I’d lived my life first on a council estate in Norwich and then growing up among working-class northerners in York. Presuming myself to be out of my depth, I struggled to apply myself to Shakespeare or other remote-seeming classical texts.

Taj Atwal rehearsing a scene from Rita, Sue and Bob Too, with Gemma Dobson

One rainy winter morning I was sulking in the library, attempting to choose a play to perform for our next module and unable to find one that resonated, when I stumbled across Andrea Dunbar’s The Arbor. WOW. “This is me,” I mumbled, turning page after page. Here were words that sounded like mine, characters I had grown up with. Eager to read more I spent the afternoon on the internet soaking up Andrea’s short and shocking life of hunger, teenage pregnancy, poverty and success, and her tragic early death. She hailed from the Buttershaw Estate on the outskirts of Bradford, coming of age at a time when unemployment was at a peak of three million. Out of this despair came her words, so true, raw and unfiltered and funny.

When she wrote The Arbor, Andrea was only 15 and struggling to complete English homework. A teacher encouraged her to write a play instead. From this The Arbor was born, and after sending it to the Royal Court young writers programme, Andrea’s play received a successful run, followed by a commission that led to her second, most famous play and subsequent film.

Alan Clarke’s film of Rita, Sue and Bob Too (photo: BFI)

Rita, Sue and Bob Too is about two teenage girls and their affair with an older man. These girls came from a place where the opportunity to thrive was non-existent. I play Rita, who has no father, several siblings, lives with her mother and is Sue’s best friend. Rita instantly falls for Bob’s charm. He shows her attention and – it seems to her – the adoration she has never received. He listens to her and having never had a male role model she looks up to him and doesn’t see his flaws.

Taj Atwal in rehearsal for Rita, Sue and Bob Too, with James Atherton.

I love the complexity Andrea gives Rita. On the surface, she’s a normal 15 year old girl up for a laugh. But underneath are layers of vulnerability and naivety – she’s easily manipulated by both Sue and Bob. And she harbours an aspiration to be something more than her circumstances promise. Like Andrea, these girls came from a place where the opportunity to thrive was almost non-existent, where the only permitted ambition for a girl was to be married with kids in a nice house. Bob is quick to put down her dreams of studying to be a policewoman or travelling, and it’s because of Bob she loses the chance to pursue them.

At 15 I was resolute that I would leave my city, see the world and become an actress. I also recall an overwhelming loneliness and the hunger to be something more. That’s what drives the characters in this play – the fight to be heard, to be loved and to be more than what their situation allows them to be. Why do they feel so real? Because Andrea knew these people, lived with them, grew up with them. As with all great playwriting, parts of her are in all of her characters. She gave a voice to a community who were suffering in Thatcher’s Britain – whether they wanted it or not.

Paul Copley, Lesley Manville and Joanne Whalley in the 1982 world premiere of Rita, Sue and Bob Too (photo: John Haynes)

Andrea wasn’t unique in her experience of alcoholism, domestic abuse and underage sex and pregnancy, nor in clawing some kind of life back from it. But her voice was unique, and silenced tragically young – she was dead at 29 from a brain haemorrhage, possibly triggered by a pub fight. She’d had three plays staged at one of the world’s most famous theatres, and in practical terms it hadn’t changed the course of her life at all.

- This article was written for the Big Issue.

- Rita, Sue and Bob Too tours from September 2017 to February 2018. Find your nearest venue.

Andrea Dunbar at home on Bradford’s Buttershaw Estate in the early 80s while she was writing Rita, Sue and Bob Too. Photo: Don McPhee.

Raised on a Bradford council estate, Andrea Dunbar was just 15 when she wrote her first play, The Arbor. A drama teacher encouraged her to send it to the Royal Court Theatre, where it was first staged as a one act play in the Young Writers Festival before being expanded into a full two-act show in the prestigious main house. Andrea was still in her teens when she wrote her second play, her biggest hit Rita Sue and Bob Too: it was commissioned when she was 19.

In case that doesn’t make you feel under-achieving enough, here’s a look at some more writing prodigies. With thanks to Kelly Slade.

ALEXANDER POPE (1688 – 1744)

Pope wrote his first poem, “Ode to Solitude,” in 1700 at the age of 12. He suffered from ill health following a childhood illness and had a curved spine, asthma and headaches. He also had a disjointed education due to his illness and tough laws against Catholics. According to his sister, all he did was write and read.

His first major work, Pastorals, was published in 1709, and brought him instant fame at 21. His most well-known poem is The Rape of the Lock, a satirical look at a high society quarrels in a pastiche of a heroic epic.

Pope eventually gained great financial success and is the third most frequently quoted author in The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations behind Shakespeare and Tennyson. He died in 1744.

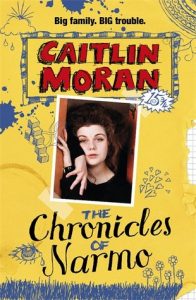

CAITLIN MORAN (b. 1975)

Caitlin Moran on the cover of her novel, which she wrote when she was 15.

Caitlin Moran’s novel The Chronicles of Narmo was published when she was 16 – the same age at which she became a reporter for Melody Maker. She grew up in a council house in Wolverhampton and was home educated, an upbringing that inspired her sitcom Raised by Wolves.

Moran – she pronounces her first name “Catlin” – is a Times columnist and has published several books of memoir, journalism and fiction, including How to be a Woman and How To Build a Girl.

BARBARA NEWHALL FOLLETT (1914 – ??)

Barbara was an American child prodigy novelist. Her first novel, The House Without Windows, was published in January 1927, when she was 12 years old and her second, The Voyage of the Norman D., received critical acclaim when she was 14.

In December 1939, aged 25, she reportedly became depressed with her marriage and walked out of her apartment with thirty dollars. She was never seen again, and later investigations failed to find trace of her alive or dead.

BRET EASTON ELLIS

The American Psycho author wrote his first novel Less Than Zero when he was 21 – the movie rights were sold before the book was published. He published his second, The Rules of Attraction, at 23.

JEAN NICOLAS ARTHUR RIMBAUD (1854 – 1891)

Rimbaud’s poem “Les Étrennes des orphelins” (“The Orphans’ New Year’s Gift”) was published in Revue pour tous when he was just 15. Having been raised by an ambitious mother who would punish his academic mistakes by depriving him of meals, Rimbaud became the image of the romantic rebel poet. At 16, he wrote “Le Bateau ivre,” which he sent to the poet Paul Verlaine as an introduction. At Verlaine’s invitation Rimbaud travelled to Paris and began an affair with the older poet, who abandoned his wife and child when the two men moved to London.

When he was almost 19, Rimbaud returned to Paris; when Verlaine later joined him, the reunion did not go well, and Verlaine shot at Rimbaud in a drunken rage, hitting Rimbaud in the wrist. (As a result of the ensuing police investigation into the attempted murder as well as the two men’s relationship, Verlaine received a 2-year prison sentence.)

Around the same time, Rimbaud published Une Saison en Enfer, his first and only work published by himself. By age 20, Rimbaud had given up creative writing for good. When he was 21, he enlisted in the Dutch Colonial Army, but deserted once he got to the Dutch East Indies.

ANYA REISS (b. 1991)

Anya Reiss’s debut Spur of the Moment in its Royal Court production. Photo: Keith Pattison.

An alumni of the Royal Court’s Young Writers Programme, Reiss was 17 when she wrote Spur of the Moment, for which she was named Most Promising Playwright at both the Critics’ Circle and Evening Standard awards. (She received her A-level results during the play’s Royal Court run!). As well as subsequent plays and Chekhov adaptations, Reiss has been a frequent writer for Eastenders.

See Rita, Sue and Bob Too on tour from September 2017 – February 2018.

]]>

Jack Nicholson and Tom Cruise in the film version of A Few Good Men

A FEW GOOD MEN by Aaron Sorkin

Daniel Kaffee is an inexperienced military lawyer, assigned to defend two US marines accused of the murder of a fellow marine at Guantanamo Bay. Over the course of the trial, the defence unearth a wider conspiracy around the murder, establishing the existence of a “code-red’ order – an extrajudicial punishment beating.

The play was inspired by real events and several people have claimed to be the “real” Kaffee, though Sorkin has said the character is not based on any one individual.

The Headlong/Almeida produciton of The Last Days of Judas Iscariot

THE LAST DAYS OF JUDAS ISCARIOT by Stephen Adly Guirgis:

Guitgis imagines a court cae to determine the fate of Jesus kisser/betrayer Judas Iscariot. The play uses flashbacks to an imagined childhood, and lawyers who call for testomines from people such as Mother Teresa, Saint Monia, Sigmund Freud and even Satan.

THE MERCHANT OF VENICE by William Shakespeare:

Shylock, a Jewish moneylender, quite literally demands a pound of flesh from merchant Antonio as the price of failing to repay a loan.

Bafflingly, Antonio agrees: the loan is to help his dear friend Bassanio pursue marriage. When Antonio’s ships fail to come in, Shylock takes him to court to demand his due. Why be lenient when he has been treated appallingly by Antonio and his circle for years?

Bassanio’s new wife, Portia, poses as lawyer and takes to the court, finding a loophole in the particular wording of the agreement, arguing that Shylock may take his pound of flesh but if any blood is shed, or the weight taken is not exactly a pound, or any harm comes to Antonio, Shylock will lose his fortune – and his life.

THE ACCUSED

Jeffrey Archer’s third play cast the audience as its jury, and himself as Dr Sherwood, accused of murdering his wife. Two endings were prepared, depending on the audience’s vote.

TWLEVE ANGRY MEN by Reginald Rose:

Twelve nameless jurors must decide whether a young man killed his own father.

The stakes are high: during the play the jury are told if they reach a guilty verdict, it will result in the death sentence.

Twelve Angry Men explores the roles of race and class within a justice system that depends on the willing participation of its citizens. The play was adapted from Rose’s original teleplay of the same title in 1954 and made its Broadway debut fifty years later.

To Kill A Mockingbird, at Regents Park Open Air Theatre

TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD by Harper Lee:

Lawyer Atticus Finch is appointed to defend Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping a young white woman – an impossible task in the social climate, despite the significant evidence supporting Tom’s innocence. Lee’s genius move was to tell her Depression-era story through the eyes of Scout, Atticus’ young daughter.

The best-known adaptation of Harper Lee’s novel is the 1962 film, but the 1990 stage adaptation has been performed widely including a 2013 production starring Robert Shawn Leonard.

THE CRUCIBLE by Arthur Miller:

Three girls and a black slave are caught dancing in the woods by local minister Reverend Parris, whose daughter has fallen into a coma-like sleep.

Rumours of witchcraft fly about, and the resulting persecutions and trials engulf the town. But more earthly secrets complicates the proceedings, not least the past affair between one of the young women and John Proctor, a local farmer who is eventually hung for witchcraft, having refused to make an official confession that might save his life.

The Crucible is set amid the witch trials of Salem, Massachusetts in 1692. Miller wrote it during the administration of Senator Joseph McCarthy, to whose House Committee on Un-American Activities Miller had testified, but refused to name suspected Communists.

Kevin Spacey in Inherit The Wind at the Old Vic

INHERIT THE WIND by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee:

Highlighting the cultural clash between science and religion, Inherit the Wind follows the trial of Bertram Cates, who has been arrested for teaching Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution. The small-town court case draws national attention with lawyers and journalists flocking in from all around.

It was based on the 1925 trial of teacher John T Scopes in Tennessee USA. In 1922, a legislator from Tennessee had argued that since the bible provided the basis for the American government any deviation from it constituted as disrespect to the law.

The play gets its title from the Book of Proverbs which says, “He that troubleth his own house shall inherit the wind; and the fool shall be servant to the wise of the heart.”

THE WITNESS FOR THE PROSECUTION by Agatha Christie:

[SPOILER!]

A young man named Leonard Vole is arrested for the murder of Emily French, a wealthy middle-aged woman with whom Leonard has had an affair and who has made Leonard her principle heir.

Leonard’s wife Romaine testifies in the trial, not to his defence but as a witness for the prosecution. At first, her testimony seems a damning indictment that will see him hanged. But some of her evidence proves fabricated, and the case against Vole collapses. It is, however, a deliberate ploy: by playing an unreliable witness, Romaine secures her husband’s freedom.

Christie’s play was first published as a short story, and she revised the ending more than once.

A MAN FOR ALL SEASONS by Robert Bolt:

Sir Thomas More was the Chancellor of England in the 16th Century. He was charged with treason for refusing to approve King Henry VIII’s wish to divorce Catherine of Aragon in order to Marry Anne Boleyn. At trial he is found guilty, and the town gathers to see him beheaded.

The Catholic martyr’s life and trial are also the subject of Thomas More, a play written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle with contributions from other writers including William Shakespeare.

LEGALLY BLONDE THE MUSICAL by Laurence O’Keefe, Nell Benjamin and Heather Hach:

Based on the novel written by Amanda Brown and after the success of the 2001 film, Legally Blonde The Musical was nominated for seven Tony Awards and won three Olivier Awards. It tells the story of Elle Woods, a sorority girls who follows her ex-boyfriend in enrolling at Harvard Law in a bid to win him back by attempting to appear more substantial. At first look, people have little faith in Elle’s abilities, but much to their surprise in a dramatic court case Elle successfully defends exercise queen Brooke Wydham in a murder trial against her rich, older husband.

CHICAGO THE MUSICAL by Fred Ebb, Bob Fosse and John Kander

In 1924, reporter Maurine Dallas Watkins covered two unrelated murder trials, both of which featured a woman who had been accused of murdering a man. Both women were acquitted. She adapted the stories into a play, Chicago, which was much later adapted into the far better known 1975 musical.

Chicago exploits the jazz-age backdrop to the events in its music, and explores society’s expectations of women.

A MAN IN THE GLASS BOOTH by Robert Shaw:

Holocaust survivor Arthur Goldman is now a rich and eccentric industrialist living in luxury in Manhattan. He is kidnapped by Mossad, and taken to Israel to be tried as a Nazi war criminal, accused of running the death camp at which he claimed his family were killed.

Goldman’s own extraordinary defence at trial draws on myriad and far-reaching cultural and historical references, and leaves his identity in question till the end.

Shaw’s play, based on his 1967 novel and adapted with the help of Harold Pinter, was inspired by the trial of Adolf Eichmann.

The Scottsboro Boys at the Young Vic

THE SCOTTSBORO BOYS by John Kander, Fred Ebb and David Thompson

In the infamous Scottsboro boys trial of 1931 nine African-American teenagers were accused of raping two white American women on a train. Their accusers make the accusation as a distractive ploy after being recognised as prostitutes by the police. So begins a painfully long trial process, in which their first defence lawyer is useless and a drunk.

THE TRIAL OF GOD by Elie Wiesel:

Three minstrels arrive at an inn in the city of Shamgorod. It is Purim, a holiday commemorating the defeat of a planned genocide against Jews. But when they discover that all the city’s Jews have been massacred except for the innkeeper, they decide to put their God on trial for allowing such carnage.

]]>

“Keep on writing, even if it’s crap. You can always throw it away later”.

Maybe all writing advice boils down this bit of practical wisdom from Alistair Beaton. We spoke to Alistair and other successful playwrights to ask them about the business of writing. Where does inspiration come from? When is the best time of day to write? What do you do if you get stuck?

Whether you’re a writer, trying to be a writer or are just interested the creative process, we hope you find insight and encouragement. If you’d like to read more, you’ll find the full interviews on the WiT Award website.

ON GETTING STUCK

“Stuck, to me, just means it’s hard, it’s not fun, you don’t want to suffer the shame of writing something terrible… but you just have to get it out, get through it, accept it won’t be perfect the first time”

James Graham (This House)

“Keep on writing, even if it’s crap. You can always throw it away later.”

Alistair Beaton (Feelgood)

“Getting stuck is the sign that I need to step back and create thinking space. It also means that the story might not have the legs I initially thought it had.”

Oladipo Agboluaje (New Nigerians)

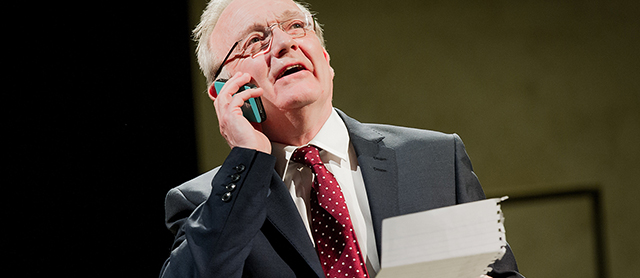

James Graham

“Stuck is not necessarily quicksand – it’s simply a refusal to move in a certain direction at that time. If I can’t write then I’ll try and watch some brilliant films”

Rebecca Lenkiewicz (Her Naked Skin)

“Often being stuck is because I’ve not thought enough about my intention. I kind of think writer’s block is an invention of people who want to think of themselves as writers but not do any work… It can be avoided by thinking and preparing properly.

Simon Stephens (Curious Incident)

“When I’m stuck I do a lot of violent self-loathing, which is unhelpful, and discussions with my husband, which are very helpful.

Lucy Kirkwood (Chimerica)

“Lots of writers clean when they’re stuck. I don’t. I probably should. I go to the coffee shop. Phone my granny. Do some yoga.”

Jessica Swale (Nell Gwynne)

“I try and write through it. I go ‘off book’ and write around the script. I try stream of consciousness writing in character, or write scenes that I know aren’t part of the story I’m writing but that help to unlock the characters a bit more for me. Sometimes I like that stuff more, and it ends up going into the final piece.”

Suhayla El Bushra (The Suicide)

Stella Feehily

WHERE INSPIRATION COMES FROM

“The news. And the past”

James Graham

“I write satirically, so I riff off news stories and I observe people and situations.”

Oladipo Agboluaje

“Galleries and museums can be very helpful, so can talking to people. I try to follow my obsessions because if you can’t stop thinking about something you might have to write about it.”

Dawn King (Foxfinder)

“I find a lot of inspiration in true stories. I always think I should keep a notebook of ideas and never do. People’s acts of bravery I find inspiring”

Rebecca Lenkiewicz

Suhayla El Bushra

“Previous inspiration has come from teenagers I’ve worked with, my dad, my mum, my upbringing, history books, Greek tragedies, fiction, cinema. Some music videos I find really inspiring. Listening to music while running. Eavesdropping on conversations on trains and buses.”

Suhayla El Bushra

“Blue Stockings, my first play, came from a detail in the research I was doing on another project entirely. I was reading about the life prospects of women in the 1800s to help an actress with her character, and I stumbled across the fact that women weren’t given access to University. The whole thing grew from there.”

Jessica Swale

“People talk about inspiration like an event but I think it is more of a cumulative thing, the gradual synthesis of different ideas and emotions and ambitions until there is something interesting and concrete enough to provoke a play.”

Lucy Kirkwood

“My inspiration usually comes from a feeling that there’s more to something than meets the eye, and I want to find out what that is. I also have an inbuilt distrust of authority and want to know what’s really going on.”

Robin Soans (Talking to Terrorists)

WHERE AND WHEN TO WRITE

“I split up working at home and working out of the house in cafes, because I get bored of being in the same place and I find if I move locations I can often squeeze out another couple of hours.”

Dawn King

“Usually after the 10 o’clock news and then through to the early hours. I’m often close to a state of dreaming. I’m not sure how helpful that is though. Sometimes I fall asleep…”

Stella Feehily (This May Hurt A Bit)

Oladipo Agboluaje

“I have a lot of creative mental activity in the fuzzy area between sleeping and waking, and so have a burst of outpouring when I first reach the computer, probably before breakfast… I will go on writing through the day, but that initial burst is always the best and most productive. I usually write to music: Always Bach in the morning, then through Handel, Mozart, Haydn, Mendelssohn, into Schubert and Mahler, Verdi, Tchaikovsky late afternoon, and if I’m burning the midnight oil, either Elizabethan polyphonic music, Plainsong, or Indian mystic music.”

Robin Soans

“I write any time of day. I’m more of an inspiration than a perspiration writer. If the spirit doesn’t move me, no time of day is ideal.”

Oladipo Agboluaje

“I rent a portacabin… it has far less distractions than at home. Cafes can be good; trains if my brain says yes.”

Rebecca Lenkiewicz

“Nine o’clock till lunch weekdays when it goes badly; nine till five weekdays when it goes well”

David Hare (Plenty)

“I can write anywhere. At the moment I am enjoying writing in my kitchen with my puppy at my feet”

Simon Stephens.

PROCRASTINATION

“I’m addicted to Facebook. It can be a nice break if you work from home as it’s the equivalent of having a chat around the water cooler, but you can end up staring at the screen numbly scrolling, or wasting time and energy arguing with people you don’t know very well about contentious political issues or what the best Bananarama single was.”

Suhayla El Bushra

“I don’t have a smartphone and only check emails once a day – sometimes once every couple of days if I am really in the trenches with something. This isn’t something I’m proud of, I think other people find it easier to juggle things”

Lucy Kirkwood

Jessica Swale

“I realised a short time ago that procrastination was a fundamental part of the job. I set myself rigorous deadlines and compartmentalise the objectives of each working day strictly according to meet those plans. I know what I want to achieve each day. I can procrastinate as much as I like as long as I hit those objectives. Sometimes the objective might be writing a number of scenes. Sometimes refining a plan or doing a redraft. But I never miss the objective.”

Simon Stephens

“I give myself restrictions. So, for example, I will only read three of the ten Guardian leading news stories before I start work. I’ll answer one email but will not get distracted by funny videos on You Tube… I’ll review what I’ve already written but if I’ve got a distance to go I won’t allow myself to edit – I keep going. Plus, I sort of believe in procrastination. Sometimes an idea pops up when you are unnecessarily dusting the skirting boards.”

Stella Feehily

ON CALLING YOURSELF A WRITER

“I still blush or feel like a fraud when I have to say what I do now to strangers. I don’t know why. No one should.”

James Graham

“My first review ever was in Plays and Players. “The most pointless evening I have ever spent in a theatre”. I knew I was a writer then.”

David Hare

Robin Soans

“Getting the type-set proofs of my first play from Nick Hern Books. It was very exciting. It was the first time that I felt like a writer.”

Stella Feehily

“I remember being asked my profession was when I registered at a new doctor’s in 2000, and I was resident dramatist at the Royal Court and I said “writer” and that felt great.”

Simon Stephens

“I remember hearing my name on the radio for the first time, following a sketch I had written, and was stunned with what felt like sudden fame.”

Alistair Beaton

WHEN IS A PLAY FINISHED?

“You never know. That’s why deadlines are essential. They stop you from tinkering and force you to commit.”

Simon Stephens

“When intelligent actors can’t find any more questions to ask. The greatest moment in playwriting is when the actors take it out of your hands.”

David Hare

David Hare

“It never really is. I sit there at the first night noticing the little things I should have improved”

Alistair Beaton

“When your actor says ‘I don’t want anymore lines’.”

Stella Feehily

“You can tell when a draft is finished. That’s usually when you feel you’ve done all you can for now and you need someone else to cast a fresh eye on it. But I don’t know that a play ever feels finished… you just have to let it go and move on to the next project.”

Suhayla El Bushra

“A play is only ever the recipe not the finished cake. But I know when it’s ‘finished’, as in I’ll let people look at it and judge it when I can’t think of anything else to do to it to improve it.”

Dawn King

“A reticence to change any of it is the closest I can feel to “it’s finished.” When you’re moved by it and you don’t want to change it, it’s a good guide to down tools.”

Rebecca Lenkiewicz

Find the complete interviews on the WiT Award website.

]]>

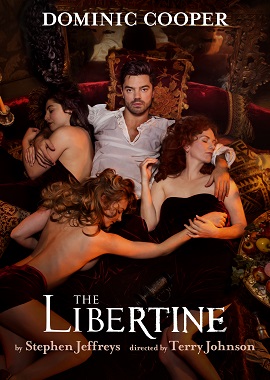

Out of Joint and the Royal Court’s production of The Libertine. Photo by John Haynes

Our artistic director MAX STAFFORD-CLARK introduces three plays which started life as Out of Joint commissions, and are now shining bright in new productions this autumn.

It’s always validating when a play you commission gets a further life and becomes part of the national repertoire. And strange, too, seeing someone else’s take on something I’m that close to.

This autumn there are major revivals of three plays that were commissioned and first produced by Out of Joint. The Libertine by Stephen Jeffreys comes to the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, with Dominic Cooper in the title role. Caryl Churchill’s experimental Blue Heart is being produced by Bristol’s Tobacco Factory and the Orange Tree in Richmond. And the Lyric Hammersmith is giving a big new production of Shopping and F***ing by Mark Ravenhill.

SHOPPING AND F***ING by Mark Ravenhill

Out of Joint and the Royal Court Theatre’s production of Shopping and F***ing. Photo by John Haynes.

I went to a scratch night of new theatre writing, at which Mark presented a short play called Fist. Twenty minutes, very rude. I don’t remember much more than that apart from thinking he had a fresh voice and could command attention.

I told Mark, if you ever write something longer, send it to me. He said that he already had something he’d show me. I heard nothing for months so I decided to seek him out – I tracked him down to the Salisbury Playhouse education department where he was working. “Where’s my play?” He’d been lying – there was no play. But eventually he got a draft together and sent it to me, and I gave him £250 or something to develop it.

I had to do some convincing. Sonia Friedman, who was Out of Joint’s founding producer, was dead against it because she thought it would ruin our chances of any Arts Council funding. It started at the Royal Court upstairs, playing to fifty-something punters a night, and went on to play two West End runs. But perhaps more remarkably, I can see from my diary that on its first tour, Shopping and F***ing also played to over 350 people a night in Bury St Edmunds.

Meet Mark and Max at Out of Joint’s special fundraising event on 3 November

Buy Mark Ravenhill: Plays 1 at a special price from our shop.

David Moorst and Alex Arnold rehearse in the Lyric Hammersmith’s production of Shopping and F***ing. Photo by Helen Murray

Sean Holmes, director of Shopping & F***ing at the Lyric Hammersmith:

I’d seen Max’s production but I hadn’t read it for a long time and I was taken by how prophetic it is. One of the characters talks about how there used to be big stories and big ideas, but now we’re making up our own little stories instead. That’s become true with the way we present edited versions of our lives on social media.

We’re a lot further on now from the fall of the Berlin Wall than when it was written. We live in a world with one system now, global capitalism, and that affects our behaviour and responses, whether that’s Trump or Corbyn or radical ideologies.

It remains a shocking play, but it’s not as violent or even sexual as people think. It’s the humour and the message that are subversive. I’m not directing it as a period piece. That doesn’t mean we’re filling it with iPhones, but we’re making a world that reflects today’s concerns. We’re transforming the auditorium and stage into a big studio or arena, so it’ll be very presentational, very aware of the audience.

Meet Sean, Mark and Max at Out of Joint’s special fundraising event on 3 November

THE LIBERTINE by Stephen Jeffreys

Johnny Depp in the 2004 film of The Libertine

Poster for the 2016 production of The Libertine

I’ve enjoyed pairing new plays with revivals of classics a number of times and in this case I wanted to do something about the second Earl of Rochester to play in rep with the restoration play The Man of Mode.

Rochester had been the model for that play’s rakish central character, Dorimant. He was a courtier to Charles II, and a writer of brilliantly robust poems. His A Ramble in St James’s Park begins “Much wine had passed, with grave discourse / Of who fucks who, and who does worse”. I was going to commission Heathcote Williams, and mentioned the idea at a Royal Court script meeting. Stephen Jeffreys was also on the literary team and he jumped in saying “No that’s my area Max. Let me do it.”

It was later made into a film starring Johnny Depp, though for me nothing will beat David Westhead’s performance in our production.

BLUE HEART by Caryl Churchill

Out of Joint’s production of Blue Heart. Photo by Donald Cooper

I’d worked with Caryl on Top Girls and Serious Money at the Royal Court – they were both big hits – and before that, Cloud Nine with Joint Stock. When I commissioned Blue Heart there was no brief or suggestion on my part, just an invitation to Caryl to write something for us.

The script, which consisted of two short plays, was a surprise. Heart’s Desire is about the anticipated arrival of a woman coming home to visit her family from Australia where she has lived for many years. Blue Kettle is about a conman who seeks out women who gave up children for adoption and convinces them that he’s the son they gave away. Good dramatic situations, both, but what distinguished them was the way the plays themselves begin to break down or implode, as though there was a bug in the text – and because of that you became very aware of the text itself.

In Blue Kettle, the language becomes corrupted as the words “blue” and “kettle” start to replace the words that you’d expect until the language becomes meaningless. In Heart’s Desire, the play keeps restarting or “resetting” to earlier points in the story, with surreal moments intruding. At one point, gunmen break in to the very domestic scene. Later, characters answer the door to find an ostrich waiting to enter – probably the best costume I’ve ever commissioned.

There’s also a brief moment when a crowd of children run on shrieking and run off again almost immediately, so I had to rehearse a dozen kids in every venue we toured to – and we did a substantial international tour. An observation: the kids in Catholic countries were very well behaved. Finnish children were chaotic, perhaps because they start school later. In Israel it was like directing the Old Testiment. “Rebecca, come out of that cupboard. Ishmael, stop chasing Malachi…”

Blue Heart marked the beginning of a period of formal experimentation for Caryl that has continued even to her most recent plays. She talked at the time of “anti plays”. You could call Blue Heart “the plays that go wrong”.

The 2016 production of Blue Heart by Tobacco Factory Theatres and the Orange Tree Theatre, Richmond. Photo by The Other Richard.

David Mercatali, director of the 2016 revival:

I was told about Blue Heart by Out of Joint alumni Barney Norris two years ago. I read it and thought ‘I have to get this on, it’s extraordinary’. It’s a huge logistical challenge, but the Orange Tree and Tobacco Factory Theatres were brave enough to take it on. It marked a change in direction for Caryl and you can see the influence on work like Escaped Alone. I wanted to bring it back into the conversation. The plays are like much of Caryl’s work: a simple conceit presented in such a bold, theatrical way that your brain goes on overload. I felt I had got a handle on them when I first read them, but a conversation with Caryl where she mentioned the word ‘virus’ made things much clearer. I’ll say no more than that!