Kathryn O’Reilly has returned to Out of Joint to give a widely-praised performance as the ferocious, damaged, and very funny Liz Morden in Our Country’s Good. Here she talks about her character, the play’s messages and her own experiences of the power of theatre.

“Punishment is not for revenge, but to lessen crime and reform the criminal”. Elizabeth Fry (1780-1845)

It can take one person to help change someone’s life, or steer them in the right direction. When I was at school, and they were trying to chuck me out, I went to my first drama teacher for help. The head of the board of Governors asked me, “what do you want to be when you grow up?” “An actress” I replied. The head scoffed and said “I suppose we think we have another Emma Thompson on our hands.” My drama teacher was very encouraging and I found drama such a positive way to channel my energies.

Theatre has had a massive and positive impact on my life. Prior to training at LAMDA, I spent years working in forum theatre and role playing in equality and diversity work. I worked for the NHS, the Police, and ran my own children’s theatre company.

Theatre has had a massive and positive impact on my life. Prior to training at LAMDA, I spent years working in forum theatre and role playing in equality and diversity work. I worked for the NHS, the Police, and ran my own children’s theatre company.

Our Country’s Good asks massive questions about society, crime and humanity that I find absolutely fascinating. Its great theme for me is the power of theatre in changing, inspiring and educating lives. I believe passionately in this power of the theatre and the arts.

I play a character called Liz Morden, a convict who comes across as pretty intimidating when she first joins the cast of The Recruiting Officer in the play. Liz had virtually no chance from the off. Her journey from victim to perpetrator is incredibly interesting. Of course, not every person who suffers like Liz turns to crime and ends up behind bars but it is easy to see how it happens. And it makes sense to Liz too: by the time in the play when she is arrested for stealing food, and put into prison within the colony – a prison within a prison – and facing death, it seems inevitable, as if everything in her life has been leading up to this.

Liz’s story is timeless. She was born into extreme poverty, with a broken home life and no formal education. A lack of positive role models, of love, care, affection and encouragement. She has to grow up very quickly. She’s betrayed and abandoned by her family. She enters a life of crime. Sentenced and imprisoned.

When she was still a child, her own father betrayed her: he shifted the blame to her very publically for a theft in order to save his own skin. She was beaten and humiliated in the street , with no one running to her aid, and so this traumatising experience further fuelled in her feelings of low self-esteem, a confused sense of identity, fear and rage and . In that moment of betrayal, her chances and choices in life were suddenly and dramatically shrunk. Liz also feels deeply unattractive. Her own brother tells her to her face she is ugly and he plants the seed that she can earn money by going on the game, suggesting that, after all, most men don’t look at the mantelpiece. This is further rammed home by her pimp who tells her as she ages to supplement, or “spice”, her dwindling earnings by following in her father’s footsteps to be a “nibbler”, or small-time thief.

When she was still a child, her own father betrayed her: he shifted the blame to her very publically for a theft in order to save his own skin. She was beaten and humiliated in the street , with no one running to her aid, and so this traumatising experience further fuelled in her feelings of low self-esteem, a confused sense of identity, fear and rage and . In that moment of betrayal, her chances and choices in life were suddenly and dramatically shrunk. Liz also feels deeply unattractive. Her own brother tells her to her face she is ugly and he plants the seed that she can earn money by going on the game, suggesting that, after all, most men don’t look at the mantelpiece. This is further rammed home by her pimp who tells her as she ages to supplement, or “spice”, her dwindling earnings by following in her father’s footsteps to be a “nibbler”, or small-time thief.

It’s easy to see, with this kind of cycle, how the idea came about that crime was (to use modern parlance) in the genes; that there was a criminal mind, even a “criminal class”. In the play, we hear Captain Tench describe the convict’s as “born that way”. Back then, when Our Country’s Good is set, the Government dealt with this criminal class by initiating the biggest single exile in history, loading them on a ship and sending them half way around the world. Out of sight, out of mind. Thinking this would eradicate them. Liz is described as “foul mouthed and lower than an animal” by officers. Times change, but the language used to write off a whole section of society doesn’t sound all that alien to our own era.

But Liz has a hero, in the figure of the progressive Governor of the colony, Captain Phillip. Whether you believe “act like a king and people will treat you like a king” or “treat someone like a king and they will act like one”, belief and behaviour has to start somewhere. Phillip believes this. That we are born free, that everyone is equal – and then life happens. “Treat her as a corpse and of course she will die” he says. Instead, “try a little kindness”. As I said, it can take one person.

Liz was played by Linda Bassett in the original production 25 years ago (no pressure!). I see her as my most prestigious role to date and I’ve had to dig deep to portray her. As an actor you have to find the character you’re playing, from the text, all the facts about them, the events, given circumstances, goals and obstacles, what other characters say about them, the language your character uses, all these go into building your creation. Working with Max Stafford-Clark he also requires us to carry out research, reading books and reporting back on interesting findings, he also sets improvisations as well as facilitating a delving into one’s own personal stories from which a parallel can be drawn and used effectively. For example, to help me find the sense of empowerment Liz gets from taking part in a play, Max asked me in rehearsals “when did you fall in love with theatre?”. I was thirteen, playing a Jet Girl in West Side Story (with my first drama teacher directing it). It was completely thrilling.

I love Liz. She has integrity, humour, and she’s a survivor. I hope you’ll enjoy meeting her too.

Follow Kathryn on Twitter @kathryn1oreilly

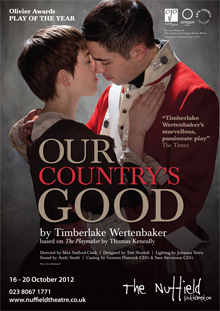

When we began to think of the poster image we might create for our publicity material, as well as rereading the play we looked at a lot of previous examples from the many productions there have been, professional, amateur and student. The majority feature either a noose, or chains or handcuffs, or perhaps a map of Australia made out of these objects. The logic is impeccable, but the images seemed to reflect the facts of the piece and not its heart. That’s why we wanted people on it – an officer and a convict, and the suggestion of their discovering a connection, a fellow humanity.

When we began to think of the poster image we might create for our publicity material, as well as rereading the play we looked at a lot of previous examples from the many productions there have been, professional, amateur and student. The majority feature either a noose, or chains or handcuffs, or perhaps a map of Australia made out of these objects. The logic is impeccable, but the images seemed to reflect the facts of the piece and not its heart. That’s why we wanted people on it – an officer and a convict, and the suggestion of their discovering a connection, a fellow humanity. Plays have strange and complex ways of getting written, that often only become clear much later. It was interesting for me to go back to the time I wrote Our Country’s Good as Max Stafford-Clark and I were auditioning recently for his new production. I found myself remembering why some things had gone into the play and even into specific lines.

Plays have strange and complex ways of getting written, that often only become clear much later. It was interesting for me to go back to the time I wrote Our Country’s Good as Max Stafford-Clark and I were auditioning recently for his new production. I found myself remembering why some things had gone into the play and even into specific lines.

Search

Search