Hywel Morgan plays NHS founder Nye Bevan in This May Hurt A Bit. Here’s his personal rehearsal journey.

‘Aneurin Bevan?, Architect of the NHS and my political hero?! I’ll bite your arm off.’

The statue of Aneurin Bevan in Cardiff.

That was what I told my agent before I’d even read Stella Feehilly’s script for ‘This May Hurt A Bit’. Despite having died twelve years before I was born, coming from South Wales, Nye Bevan is a massive figure. Robert Thomas’ life size bronze at the end of Queen Street in Cardiff appeared during my teenage years and espite sometimes being crowned with a traffic cone the morning after an International, his legacy was never obscured: ‘Aneurin Bevan 1897-1960. Founder of the NHS.’

Over the years and particularly under the current government, Nye’s excoriating quotes about the Tories and the NHS have become seared into my memory and it brought tears of joy to my eyes when Danny Boyle put the NHS centre stage at the Olympics. ‘Now let them try and privatise it’, I thought. But the Health and Social Care Bill, despite being widely reported as deeply flawed and heavily amended by both Houses of Parliament still got through.

I’d seen Max’s production of ‘The Permanent Way’ in 2005 and left the theatre burning with anger about the effects of privatisation on the railways. If I’m honest, I’d paid scant attention to the subject beforehand. I urged everyone to see it and foisted my programme playscript on people after the run had closed. From the first speech in the play, I knew ‘This May Hurt A Bit’ had the potential of sending out a similar message about the NHS.

The odds are stacked against me: Nye was ten years older than me and a little more portly in stature (a consequence of his reputation as a socialist and Bon Viveur, no doubt.) Secondly, although his political quotes are almost as well known as Churchill’s, his speaking voice is quite individual. For a barrel-chested Welshman, it was very high pitched, littered with peculiar traits and a stammer to boot. I pored over archive footage, united and actioned the speech then took myself off to Crystal Palace park to work on it. I banked that no-one would come near a ranting Welshman in the middle if a maze on a windy Thursday afternoon and I was right. By sunset, I had something approaching Nye’s extraordinary fluting pitch and delivery and a good sense of the desire to shame the BMA that drives the speech. Thankfully it was only after I’d read the speech that Max told me that they’d been workshopping the play at the National Studio since 2008 and that Neil Kinnock had been playing Nye.

I try to forget about auditions once they’re over in case it doesn’t work out. That way madness lies. When the offer comes through on Monday, I’m initially ecstatic then realise that it means my wife will have to take sole care of our little boy while I’m away on tour. He’s just turned one and up until now we’ve been able to juggle work commitments around him. Despite trying not to think about the play, Mellony tells me I’ve been lecturing her about the history of the NHS, Bevan and the threat of privatisation over the weekend. She knows how much it means to me and assures me well find a way to manage. The fact that we’ve got five weeks rehearsing in London is a huge relief. It’ll be March before I go away so we’ve got time to get our heads around it and adjust to both being full time working parents for the first time.

Hywel Morgan in rehearsal

REHEARSALS – WORKING ON THE TEXT

28th January

Day one. Greeted warmly in Welsh by Stephanie Cole who is playing Iris. It’s a lovely ice breaker.

We read through the play. By following Iris’s family, Stella explores the history and ethos of the NHS then events take us on a journey through the NHS in its current form – understaffed wards, overworked staff, fallible computer systems. It’s blackly funny, absurd in places and very sobering. The scenes all have Brechtian titles and Max describes the opening of the second act ‘Bring on the Dancing Nurses’ as a tribute to Danny Boyle’s Olympic ceremony.

29 January

Day two of rehearsals and we’re straight into “actioning” the play. This involves deciding on a transitive verb to describe our character’s intention on each line. A transitive verb is something you do to someone else, such as enlist, or tease, or provoke.

I’d already actioned the opening speech for my audition, but when we confer about the choices I’ve made, Max makes some better suggestions which give the speech much more light and shade. I’ve used actioning before but this really is a lesson from the master. It’s a brilliant framework to work within, and liberating. I wonder if it’s actions, not lines that Johnny Depp has fed into his earpiece!

By the end, Bevan’s slushy, stammering, little cornet of a voice is sweetly chiding and shaming the BMA and rallying the Labour benches with the Spirit of ’45.

REHEARSALS – MEETING THE EXPERTS

31 January

Stella and Max have invited a number of NHS experts to meet us, and today we welcome Dr Lucy Reynolds. Lucy is a Policy Strategist who used to work for large multinational companies in mergers and acquisitions. Having returned to the UK after working abroad she was horrified when she read the Health and Social Care bill and realised its implications: the bill is structured so that the NHS resembles a corporation that is being prepared for a takeover. It is being ‘harmonised’ for integration with large private healthcare insurance companies (in which over 200 sitting MP’s have interests).

If Bevan was the architect of the NHS then John Redwood planned it’s demolition under Thatcher many years ago. New Labour’s love of Private Finance Initiatives meant many new hospitals were built and although the balances didn’t appear on the books because they weren’t government funded, the public were saddled with the debt; but the NHS was further weakened by Alan Milburn who imported the Foundation Trust Hospital model from Spain. This allowed hospitals to act like businesses, to seek investment from private companies and opened the door to further marketisation of some NHS services. The New Health and Social care act utilised this change to widen the bridge of privatisation. David Cameron’s statements about ‘No top down reorganisation’ and ‘We will not sell off the NHS’ bear no relation to the act that was actually passed. It opens the door to ‘Any Qualified Provider’ being able to compete to provide services within the NHS.

Stephanie Cole and Natalie Klamar in rehearsal

The problem is that there is far more admin for both the NHS and the private companies, and the result is that money is being diverted away from patient care. The new system is 1/3 admin costs as opposed to 1/20th under Bevan. Lucy is incredibly passionate, almost shaking with fury as she talks and at the end apologises for ranting at us. It feels like a fait accompli: that the eventual demise of the NHS is inevitable, especially if the EU signs up to EU/US trade deal, (the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership or TTIP). If the NHS is not exempted from this deal it would have to operate within strict EU competition laws, meaning that the section of ‘Any Qualified Provider’ would be thrown open to the huge companies that dominate the US healthcare industry and there’s no way of reversing it.

3rd February

Lucy’s talk on Friday left me feeling quite depressed. Today we met Dr Jacky Davis, a Consultant Radiologist, and she restored my faith a little. Jacky founded the NHS National Health Action party and co-authored ‘NHS: SOS’ which I’ve been reading on the way to and from rehearsals. It has a foreword by Ken Loach and she asks us if we’ve seen his film ‘The Spirit of ’45’. We chorus ‘Yes’ and she beams: ‘Ah well, you’re already enlightened then!’

Jacky’s opinion is that Labour must make a convincing commitment to repeal the Health and Social care act, restore the Health Minister as being the person responsible for delivering a health service and taking on the debts from PFI hospitals into central Government borrowing, thereby putting it on the balance sheets but getting away from the crippling interest rates.

Finally, she tells us that we’ve lost over 50% of hospital beds over the last 20 years. There are huge shortages in acute and mental care wards as a result. The weakest and most vulnerable in our society are paying the price of austerity. Jacky is convinced that the NHS will be a major factor in the 2015 elections and is delighted that we’re doing this play.

4 February

In This May Hurt A Bit, one of the characters has a fit, and the ward staff have to respond. So today Dr Polly Brown, a Junior Doctor, took us through the anatomy of a medical emergency. In the play, “Doctor Gray” is on the ward doing rounds. Being the first person on the scene, she would take charge unless someone of a higher grade arrived, and would call for members of the on-duty Medical Emergency Team.

The Junior Doctor roleplays the situation for us, joining in the scene. Franc, who is playing Dr Gray, and Stella take notes. It’s very jargon heavy – we end up talking in acronyms – but shorthand is needed when time is short, and the emphasis is on a calm response and clear communication.

The thing is, we’ll be acting this out every night, knowing exactly what’s happening to our patient and that he’ll survive. In the real world, we wouldn’t know.

5th February

The most scary day for me so far. Max and Stella have invited Neil Kinnock to rehearsals. Neil is a direct conduit to Nye Bevan. They’re both from Tredegar, Nye was Neil’s hero and Neil is one of mine. Having hoped to join us in the morning he finally bursts into the rehearsal room at 5, throws his head back and booms a four letter word in frustration and apology for the delay. There’s a tube strike and it’s taken him four hours to get from Westminster to Finsbury Park. It’s raining but he’s dropped Glenys off to walk the rest of the way home.

He throws himself enthusiastically into meeting everyone. I shake his hand, which is cold, and introduce myself. ‘Where you from, kid?’ he beams back. It’s like speaking to my Uncle. He banters with me about familiar places and ends up confessing he crashed a car in Skewen once, (not his fault he assures us.)

Neil is here to give me notes on how I’m playing Nye, in front of the entire company. He’s relaxes and staring at me through his glasses. I’m not sure if I know the words yet, and I panic and launch into a torrent of high pitched Welsh shouting. All the subtlety, rhetoric and light and shade that I’ve worked on with Max and Stella goes straight out the window.

Neil is kind, tells me where I’m on the right track, enlightens me on a part of the speech that I’d misinterpreted and gives me notes about Nye’s stammer, which he says was caused by ‘a bastard of a teacher’. He surprises us all by explaining that this speech was delivered in the House of Lords because the commons was bomb damaged and says that Nye ‘always started small and finished big’.

Max gets me to do my party piece of impersonating Tony Blair before we finish. I oblige. Neil chuckles and tells us that cartoonists and impressionists are still having real trouble capturing Cameron because he’s so anonymous.

6th February

Following our roleplay of the MET call (which Stella has now honed into a taut scene worthy of E.R.) today we’re visited by Alan who’s been a paramedic in London for many years. We launch into a scene and within seconds he’s stopped us. ‘Sorry, you just wouldn’t be that rude to members of the public’ he says.

Alan takes us through the whole process from making the phone call to the emergency services to arriving at hospital. We ask Alan about what effect the cuts have had on him. He says there are less hospital beds now which means A&E departments get backed up and are often working way beyond their capacity. As he’s waiting for his taxi at the end, Max starts an exercise in the rehearsal room which involves the use of a lot of expletives. Alan glances back though the door to see Stephanie Cole cursing at other company members. He is horrified, Stephanie is in stitches.

7th February

Dr Louise Irvine was the driving force behind the Save Lewisham Hospital campaign. She explains how, despite being financially solvent, Lewisham Hospital was under threat of closure recently. A nearby Healthcare Trust had gone into administration and the Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt had tried to downgrade Lewisham Hospital’s A&E in order to balance the books. The move prompted a huge public campaign which culminated in a legal challenge to the government. They won a landmark judgement, the government appealed and lost but the fight is not over – the Government are now trying to amend the law itself. If they manage to do so, it will give the health secretary the power to close any hospital in the country without consultation.

Lewisham is my nearest A&E and they have a fabulous Children’s A&E there so it was lovely to be able to express my deep gratitude to her for saving our local hospital from closure. Turns out Louise is also Franc’s G.P. These are people at the coal face fighting for the longevity of the NHS and gathering huge public support. Louise and all the people in the campaign are living proof of Nye Bevan’s words: ‘The NHS will survive as long as there a folk left with the faith to fight for it.’

REHEARSALS – A DAY AT THE HOSPITAL WITH “JJ”

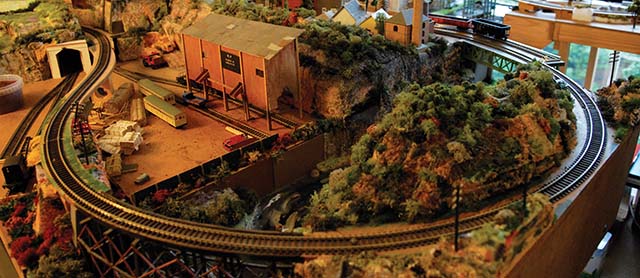

London’s Whittington Hospital

Today I had the privilege of meeting a man who for me embodies the very spirit of the NHS. ‘I wish you’d been here yesterday’, he tells me, ‘You’d have met someone important.’ He’s referring to Ed Milliband, who’d been at the Whittington Hospital the previous day. John James or ‘JJ’ McConnell has been working in the NHS for thirty years. Smartly turned out in a well-ironed pale blue shirt, black trousers and sensible shoes, he sports an ID lanyard and a small container of hand gel which hangs off his belt.

JJ started off in operating theatres and for the last seven years has been proud to be ‘Front of House’ at the Whittington. From his little cubby hole just off the main entrance to the Whittington, JJ has a panoramic view of everyone that arrives at the hospital. Even before they’ve entered the building, he has been watching patients arrive and assessing if they need assistance. As a result he is often at the front door to greet them as they arrive. He has several types of porters chairs, decorated in hazard tape and postcards of London. ‘to stop taxi drivers taking them by mistake’ he explains.

JJ’s calm demeanour and gentle inquiries mask an expert ability to assess people on sight. His years of experience mean that he gets people where they need to be with the minimum of fuss and the with the maximum of discretion and care. During the couple of hours I spend with him, we deal with several patients, (one infirm, another needing emergency care and a third routine but elderly.) All of them come back to thank him before leaving the Whittington.

What does he think of the cuts to hospitals? He describes a hospital as a body, with A&E at its heart. ‘Once you close the A&E, that cuts off the blood supply to the hospital. You lose the supply of patients to Intensive Care Units so they’re next to go and eventually you end up hacking off all the limbs until there’s nothing left.’ It’s reminiscent of Bevan’s final lines in the play, comparing the NHS to Lavinia in Titus Andronicus.

In his time at the Whittington, JJ’s been voted employee of the year, been invited to Downing St and had glowing letters of praise from people he’s helped. Although he’s proud of these achievements, (he keeps copies in a carrier bag in his locker) he doesn’t crave the attention. ‘I don’t like the thought that people are scrutinising me’ he says, ‘I just want you to go away with the truth.’ I feel impelled to give him a huge hug before I leave. He truly is a gentleman.

You’ve been involved in rugby most of your life. Are you still playing?

You’ve been involved in rugby most of your life. Are you still playing? You’re the “face and voice” of Welsh Rugby Union at the Millennium Stadium. How did that come about? And – commiserations! – what was the atmosphere like at England v Wales in the Six Nations last week?

You’re the “face and voice” of Welsh Rugby Union at the Millennium Stadium. How did that come about? And – commiserations! – what was the atmosphere like at England v Wales in the Six Nations last week? Where in Wales are you from, and what’s it like there?

Where in Wales are you from, and what’s it like there?

Theatre has had a massive and positive impact on my life. Prior to training at LAMDA, I spent years working in forum theatre and role playing in equality and diversity work. I worked for the NHS, the Police, and ran my own children’s theatre company.

Theatre has had a massive and positive impact on my life. Prior to training at LAMDA, I spent years working in forum theatre and role playing in equality and diversity work. I worked for the NHS, the Police, and ran my own children’s theatre company. When she was still a child, her own father betrayed her: he shifted the blame to her very publically for a theft in order to save his own skin. She was beaten and humiliated in the street , with no one running to her aid, and so this traumatising experience further fuelled in her feelings of low self-esteem, a confused sense of identity, fear and rage and . In that moment of betrayal, her chances and choices in life were suddenly and dramatically shrunk. Liz also feels deeply unattractive. Her own brother tells her to her face she is ugly and he plants the seed that she can earn money by going on the game, suggesting that, after all, most men don’t look at the mantelpiece. This is further rammed home by her pimp who tells her as she ages to supplement, or “spice”, her dwindling earnings by following in her father’s footsteps to be a “nibbler”, or small-time thief.

When she was still a child, her own father betrayed her: he shifted the blame to her very publically for a theft in order to save his own skin. She was beaten and humiliated in the street , with no one running to her aid, and so this traumatising experience further fuelled in her feelings of low self-esteem, a confused sense of identity, fear and rage and . In that moment of betrayal, her chances and choices in life were suddenly and dramatically shrunk. Liz also feels deeply unattractive. Her own brother tells her to her face she is ugly and he plants the seed that she can earn money by going on the game, suggesting that, after all, most men don’t look at the mantelpiece. This is further rammed home by her pimp who tells her as she ages to supplement, or “spice”, her dwindling earnings by following in her father’s footsteps to be a “nibbler”, or small-time thief.

Search

Search